www.thatsbaseball.org

|

9 Innings

A Baseball Reader

Issue # 2

(July 1, 2006)

|

|

1st INNING

The Effects of Expansion

|

When expansion swelled the American League from eight teams to ten in 1961, and the National League was likewise altered a year later, the major league schedule was revised for the first time since 1904. After playing a 154-game slate for over half a century, both leagues adopted a 162-game season. Under the old schedule, every team played 22 contests against each of the other seven clubs in its loop. With two new franchises added, the number of contests teams played against their rivals was pared to 18. Expansion thereby made for a longer schedule but shorter series. Instead of ... playing four contests each time they met, teams now usually played only three per meeting. One important casualty was the traditional weekend series, which began with a night game on Friday, followed by a Ladies' Day game on Saturday and then a doubleheader on Sunday.

In 1969, a second wave of expansion, which created two new teams in both major leagues, resulted in each circuit splitting into two six-team divisions rather than balloon to an unwieldy 12-team loop. The schedule remained at 162 games, with clubs playing 18 contests against each of their five division rivals and 12 against each of the six clubs in the other division. To determine the pennant winner, it was decided that the two division champions would play a best three-of-five League Championship Series at the conclusion of the regular season. Only the World Series format was left unchanged by schedule-makers in 1969. The restructuring that was done to divide the two leagues into separate divisions resulted in several quixotic geographical arrangements .... Atlanta was placed in the National League West as was Cincinnati, while St. Louis and Chicago got spots in the East. The Chicago American League entry meanwhile was sent to the West Division ....

--1001 Fascinating Baseball Facts

David Nemec & Peter Palmer

|

|

2nd INNING

"I Beg Your Pardon"

|

My first memory of listening to Herb Score was in my basement. Herb was on the radio telling me about an Indians spring training game from Tucson or Mesa or somewhere. [S]pring training games were tough on Herb. He can -- how can this be said kindly? -- become easily confused. In the spring there are different players going in and out of the game every inning ... but Herb doesn't notice because he likes to sit with his back to the field between innings, working on his tan. But I forgive Herb. He has made a million mistakes, and so have the Indians. The only difference is that Herb is good-natured about it. On the air he sounds like the nicest guy you'd ever want to meet. Then you meet Herb, and guess what? He just may be the nicest guy you've ever met.

Herb Score has seen more Indians games than anyone, so it's no wonder he has trouble keeping things straight. Herb pitched for the Indians from 1955 to 1959. He returned to the team as a TV broadcaster in 1964, and he moved into the radio booth in 1968. That's five years playing for the Tribe and thirty more as a broadcaster.

"Herb Score has probably watched more bad baseball than anyone in the history of the game," said Joe Tait, one of his partners on radio. Maybe that's why Score's descriptions are like no others. Try some of these:

"There's a two-hopper to Kuiper who fields it on the first bounce."

"Swing and miss, called strike three."

"There's a fly ball deep to right field. Is it fair? Is it foul? It is!"

He called pitcher Efrain Valdez, "Efrem Zimbalist, Jr."

Growing up listening to Herb, then working for him for five years, Nev Chandler is a Herb Score catalog.

"One game we were playing Boston at the Stadium, and the Tribe was losing 7-4 in the bottom of the eighth," said Chandler. "The Indians had the bases loaded, two outs. Andre Thornton hit a fly ball down the left field line. It appeared to have the distance for a homer. The only question was whether it would stay in fair territory. But Boston's Jim Rice went deep into the corner, timed his leap perfectly -- I saw him catch the ball and bring it back into the park. Suddenly Herb yelled, 'And that ball is gone. A grand slam home run for Andre Thornton. That is Thornton's twenty-second home run of the year and the Indians lead, 8-7.'

"As Herb was saying this, he wasn't looking at the field. He was marking his scorebook. I saw Rice running in with the baseball. Herb was still talking about the home run. I snapped my fingers, and Herb looked up to see the Red Sox leaving the field.

"Herb said, 'I beg your pardon. Nev, what happened? Did Rice catch the ball?'

"Trying to bail Herb out, I said, 'Rice made a spectacular catch. He went up and over the wall and took the home run away. It was highway robbery.'

"Herb said, 'I thought the ball had disappeared into the seats. Well, I beg your pardon. The Indians do not take the lead. After eight innings, it is Boston 7, Cleveland 4.'

"Then we went to commercial, and Herb acted as if nothing had happened. I would have been completely flustered. But Herb just corrects himself and keeps going."

That is why Indians fans love Herb Score. He is unpretentious, making his way through games as best he can. He's just Herb being Herb, and being Herb Score sometimes means taking strange verbal sidetrips. When Albert Belle hit a home run into the upper deck in left field that supposedly went 430 feet, Score asked, "How do they know it went 430 feet? Do they measure where the ball landed? Or do they estimate where the ball would have landed if the upper deck hadn't been there? And if there had been no upper deck, then how do they know how far the ball would have gone?"

Score answered none of those age-old questions of the baseball universe. He was just wondering about it one moment, and then it was forgotten by him the next.

But not by Indians fans. One of their favorite pastimes is to tell one another what Herb said the night before. One of my favorites:

CHANDLER: "That base hit makes Cecil Cooper 19-for-42 against the Tribe this year."

SCORE: "I'm not good at math, but even I know that is over .500."

Well, it's not quite. But I'll give Herb the benefit of the doubt.

--The Curse of Rocky Colavito

Terry Pluto

|

|

3rd INNING

Polar Baseball

The Seadragon

|

On August 1, 1960, the American nuclear-powered submarine Seadragon left Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to chart a new Northwest Passage across the top of the world to the Pacific.

In the course of the historic journey, the Seadragon would become the first submarine to dive under icebergs. At one juncture, while negotiating a ticklish 850-mile passage through the Canadian archipelago, Comdr. George P. Steele consulted a 140-year-old explorer's journal. Shortly before the boat reached the North Pole, the navy briefly lost radio contact with her. On the night of August 25, 1960, the Seadragon broke through the ice at the pole and reported all was well. The crew was fine, if in need of some exercise. Skies were clear, with temperatures in the high twenties. Baseball weather.

"We have maneuvered the ship through light ice to where we can put a life raft over to to the last fifteen feet to ferry over a party to play baseball," Commander Steele radioed. "The men are wearing the warmest clothes they can get."

The 360 degrees of longitude and the International Dateline converge at the Pole. Thus the polar baseball diamond was arranged so a home run would travel "from today into tomorrow and from one side of the world to the other." A runner leaving home plate also reached first base twelve hours later. Nobody hit one into next week.

Even at the North Pole, the pastime proved to be a great equalizer: the enlisted men beat the officers, 13-10.

--Baseball Legends and Lore

David Cataneo

|

|

4th INNING

The Color of Baseball

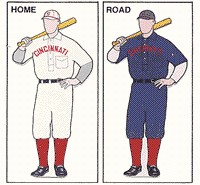

Cincinnati Reds, 1902

|

For many years baseball teams wore flannel uniforms with conservative markings -- white at home and gray on the road. But new materials and styles of the '60s -- especially public acceptance of men wearing bright colors -- returned the baseball uniform to the rainbow days of the 19th century.

The first uniformed team, the New York Knickerbockers of 1849, wore long cricket-style pants, but the first professional team, the Cincinnati Red Stockings of 20 years later, began the tradition of wearing shorter pants and long colored stockings.

In the National League's first year, the Chicago White Stockings had a different colored hat for each player, including a red, white, and blue topping for pitcher/manager Al Spalding.

At its winter meeting of 1881, the league voted to have its clubs wear stockings of different colors: Cleveland dark blue, Providence light blue, Worcester brown, Buffalo gray, Troy green, Boston red, and Detroit yellow. Position players had to wear shirts, belts, and caps as follows: catchers scarlet, pitchers light blue, first basemen scarlet and white, second basemen orange and blue, third basemen blue and white, shortstops maroon, left fielders white, center fielders red and black, right fielders gray, and substitutes green and brown. Pants and ties were universally white and shoes were made of leather.

The plan caused too much confusion and was quickly dropped, but color remained part of the game. The Chicago White Stockings wore black uniforms and white neckties under Cap Anson in 1888 and had daily laundry service. The weekly Sporting Life complained that the pants were so tight they were "positively indecent."

In 1889 Pittsburgh wore new road uniforms consisting of black pants and shirt with an orange lace cord, an orange belt, and orange-and-black striped stockings.

The St. Louis Browns, whose nickname changed to the Cardinals when their uniforms took on more red, wore shirts with vertical stripes of brown and white, complete with matching caps.

Pre-1900 styles dictated lace shirts with collars and ties, open breast pockets, and occasionally red bandana handkerchiefs as good-luck tokens. John McGraw, manager of the Giants, was the first baseball official to order uniform shirts without collars, and he also discarded the breast pockets, which sometimes served as a resting place for a batted ball.

The Giants and Phillies started the trend of wearing white at home and dark, solid colors on the road and, in 1911, the concept of whites and grays became mandatory -- partly because it was sometimes hard to tell the home club from the visitors.

In an effort to lure fans to the ballpark, Charles Finley outfitted his Kansas City Athletics in green, gold, and white suits in the '60s and invited the scorn of the baseball world. Some of his own players expressed embarrassment at playing in "softball unforms." Others likened the suits to pajamas.

But the Finley concept of color -- which included mix-and-match combinations of caps, shirts, and pants -- caught on quickly. In 1971 the Pittsburgh Pirates introduced form-fitting double knits, complete with pullover tops, and six years later designed three sets of uniforms -- gold, black and striped -- that could be worn in nine different combinations.

-- The Baseball Almanac

Don Schlossberg

|

|

5th INNING

The Amazin' Mets

|

"I don't know what's going on," Richie Ashburn said, "but I know I've never seen it before." "It" was the expansion Mets of 1962, who managed to lose 120 games under the bemused leadership of an aged Casey Stengel. Ashburn, as it happened, hit .306 that year, but no other regular topped .275. The team's best pitcher, Roger Craig, lost 24 games. The only category in which any Met led the league was errors. The Mets gave up a staggering 948 runs, some 322 more than the Pirates, who finished fourth. The team ERA was 5.04. And they concluded the season 60-1/2 games out of first place -- that is, two months out of first.

The paradigm of those Mets was Marvin Eugene Throneberry -- appropriately, his initials spelled "MET."

On June 17, 1962, Throneberry had his most memorable day in baseball. In the bottom half of the first inning in a game against the Cubs, he charged into third base with a triple, only to be called out on an appeal by the Cubs' Ernie Banks for not having touched first. That was when Casey Stengel, steaming out of the dugout to protest, was told by first-base coach Cookie Lavagetto that Throneberry had missed second, too.

It was in the top of the inning, though, that Marvelous Marv had established his pattern for the day. The Cubs' Don Landrum had led off the game with a walk, and then Al Jackson picked him off first. Landrum was caught in the ensuing rundown, but the call was negated when Throneberry was called for obstruction.

Finally, in the bottom of the ninth, with the Mets down 8-7, two men on and two men out. Throneberry came to the plate with the opportunity to redeem himself. Needless to say, he struck out.

At season's end, the Mets were 40-120. They had had losing streaks of 9, 11, 13, and 17 games. As he prepared to depart for his off-season recuperation, Throneberry asked, "You think the fish will come out of the water to boo me this winter?"

Leonard Shecter reported this exchange between Throneberry and Johnny Murphy, the old Yankee pitcher who negotiated salaries for the early Mets:

Throneberry: "People came to the park to holler at me, just like Mantle and Maris. I drew people to games."

Murphy: "You drove some away, too."

T: "I took a lot of abuse."

M: "You brought most of it on yourself."

T: "I played in the most games of my career, 116."

M: "But you didn't play well in any of them."

In a game against the Giants during the '62 Mets' 17-game losing streak. Roger Craig threw perilously close to Orlando Cepeda, and shortstop Elio Chacon took umbrage at a Willie Mays baserunning move. In short order, Mays took care of the tiny Chacon, and the 210-pound Cepeda disposed of Craig. The next morning, Newsday's coverage of the game began, "The Mets can't fight, either."

....After that first horrible season, the Mets announced they were calling up their three best minor league pitchers: Larry Bearnarth, who'd been 2-13 at Syracuse; Tom Belcher, 1-12 at Syracuse; and Grover Powell, 4-12 at Auburn and Syracuse.

Still the spring of 1963 dawned hopeful for the Mets, who were confident they were an improved team. Then the Cardinals beat them 8-0 an opening day at the Polo Grounds. Said Stengel, "We're still a fraud."

-- Baseball Anecdotes

Daniel Okrent & Steve Wulf

|

|

6th INNING

It Takes a Thief

Ron LeFlore

|

Baseball has had its share of unsavory characters, but the game's magnates have always been loath to take on players they know to have a criminal record. In the 1930s, the Washington Senators sent a shudder through the major league community when they scouted and signed a convict named Alabama Pitts. To the relief of most, Pitts proved unable to hit top-caliber pitching. Ron LeFlore recalled memories of Pitts when he joined the Detroit Tigers in 1974. A product of the Motor City ghetto, LeFlore came to the Tigers only after serving a prison stint for armed robbery that made him a persona non grata to most of the other teams in the majors. Tigers skipper Ralph Houk, though, swiftly recognized that the fleet LeFlore was the answer to the club's center field hole. In 1976, LeFlore's second full season, he led the club in hitting with a .316 batting average. Two years later he paced the American League in runs and stolen bases. Convicted of thievery, LeFlore spent nine years in the majors being paid for being a thief, swiping an average of 50 bases a season.

-- 1001 Fascinating Baseball Facts

David Nemec & Pete Palmer

|

|

7th INNING

Minnie Minoso

|

I was born Saturnino Orestes Minoso in 1922 in the small town of Perfico, Matanzaz, Cuba. I had two brothers and two sisters and was raised on a small ranch, where I cut sugarcane. I played baseball at the ranch from the time I was 11 or 12, managing the team and telling the older kids how to play. We would beat the city teams. I was a pitcher, played third, played center. I got the reputation for being the best player. I was "something else." When I first started playing, I had no idea that I'd be able to play anywhere but Cuba. My ambition was just to play professional ball in Cuba. That was every boy's dream on the island. I didn't know anything about the major leagues. My mother never saw me play professional ball because she died in 1941, a year or two before I quit high school and went to Havana. I played semipro ball for two years there, but since I got only pocket money, I worked as a mechanic for a Buick dealer. I'd get $60 a week. Then I played on the Marianao team in the Cuban Winter League. My father saw me play in my prime only in Cuba in winter ball.

I became one of the stars in Cuba and was signed to a contract by the New York Cubans in the Negro National League. So I came to the United States in 1946. I played third base and made the Eastern All-Star team in 1947, when the Cubans won the World Series, and in 1948, my last season in the Negro Leagues.

When Jackie Robinson signed to play in the major leagues, many players in the Negro League thought they had the opportunity also. I wanted to play in the major leagues to prove that I was one of the best ballplayers. I was invited to a tryout with the St. Louis Cardinals, along with a pitcher on the Cubans, Jose Santiago from Puerto Rico. We were so much better than anyone else there. Santiago struck out all 3 batters he faced, and they had to tell me to ease up on my throws because the first baseman wasn't able to handle anything so hard. But the Cardinals didn't really want to look at us. They sent us home. Because of our treatment by the Cardinals we didn't waste our time when another team invited us to a tryout. If they wanted to look at us, they could watch us play in the Negro Leagues.

--Minnie Minoso

They Played the Game

Editor's Note: Minoso played seventeen seasons in The Show, most of them with the Chicago White Sox. He was a seven-time All-Star and three-time Gold Glove (left field). His career numbers: .298, 186, 1023.

|

|

8th INNING

Jackie and the Bombers

Jackie with Ruth and Gehrig

|

On April 2, 1931, the Yankees were barnstorming north out of spring training camp when they stopped in Chattanooga, Tennessee for an exhibition game against the Southern Association's Lookouts. Chattanooga righthander Clyde Barfoot, formerly of the Cardinals and Tigers, started against the Bombers. New York outfielder Earle Combs led off with a double, and shortstop Lyn Lary followed with a run-scoring single. Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig were scheduled to follow.

Lookout manager Bert Niehoff strolled to the mound and signaled for a new pitcher. From the bullpen area in front of the right-field bleachers trotted a reliever: Jackie Mitchell, seventeen years old, a left-hander, and a girl.

The crowd of about four thousand cheered Mitchell as the Bambino stepped in to bat against the bambina. Ruth swung hard at the first pitch and missed. He swung harder at the second pitch and missed again. Ruth stepped out and demanded the home plate umpire examine the ball. The Babe stepped back in, watched the next pitch sail across the plate for called strike three, tossed his bat away in disgust, and stomped back to the dugout.

Gehrig followed and missed three straight pitches. Second baseman Tony Lazzeri tried to bunt Mitchell's first pitch but missed, then took four straight balls for a walk. Done for the day, Mitchell trotted off the mound to a hearty ovation.

Later accounts claimed the girl's appearance and the strikeouts were well-orchestrated publicity stunts, but folks were still impressed.

-- Baseball Legends and Lore

David Cataneo

|

|

9th INNING

Manager Records

|

Most Years as a Manager

AL: 50, Connie Mack, Philadelphia, 1901-1950

NL: 32, John McGraw, Baltimore, 1899, New York (Giants), 1902-1932

Most Games Won as Manager

AL: 3582, Connie Mack, Philadelphia

NL: 2690, John McGraw, Baltimore and New York

Most Pennants Won as Manager

AL: 10, Casey Stengel, New York (Yankees)

NL: 10, John McGraw, New York (Giants)

Most World Series Won as Manager

AL: 7, Joe McCarthy, New York & Casey Stengel, New York

NL: 4, Walter Alston, Brooklyn/Los Angeles

Most Consecutive Pennants Won as Manager

AL: 5, Casey Stengel, New York, 1949-53

NL: 4, John McGraw, New York, 1921-24

Most Clubs Managed to Pennants

3, Bill McKechnie, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Cincinnati

3, Dick Williams, Boston, Oakland, San Diego

First Manager to Pilot Pennant Winners in Two Leagues since 1901

Joe McCarthy, Chicago (NL), 1929, New York (AL), 1932

Only Man to Win a Pennant in His Lone Season as a Manager

George Wright, Providence (NL), 1879

Highest Career Winning Percentage as Manager

.615, Joe McCarthy, 24 seasons, 2125 wins and 1333 losses

--Great Baseball Feats, Facts & Firsts

David Nemec

|

|